John Fulton FOLINSBEE

1892–1972, USA

Biography

Discover the life and artistic journey of John Fulton FOLINSBEE (born 1892, USA, died 1972), including key biographical details that provide essential context for signature authentication and artwork verification. Understanding an artist's background, artistic periods, and career timeline is crucial for distinguishing authentic signatures from forgeries.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Folinsbee demonstrated artistic talent at an early age and was sent at age nine to study at the Albright Art Gallery. In 1906, he contracted polio and went to convalesce with his aunt and uncle, the McCutcheons, in Plainfield, New Jersey. When the family moved to Washington, Connecticut, Folinsbee enrolled at the Gunnery School, where the art teacher Elizabeth Kempton encouraged students to “go their own way”—a suggestion that apparently had a significant influence on the young artist.

John Folinsbee had committed himself to painting by 1912, and his productive career covered sixty years. Early on, Folinsbee studied with Birge Harrison and John Carlson in Woodstock, New York. He had his first work, Morning Light, accepted for exhibition at the National Academy of Design in 1913, when he was only twenty-one. Folinsbee (known as Jack) quickly became a regular exhibitor at the National Academy, where he won nearly every award—sometimes more than once.

Folinsbee married Ruth Baldwin in 1914, and, two years later, they moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania. In New Hope, Folinsbee joined the group of artists working there, which included Edward Redfield, Daniel Garber, Robert Spencer, and William Lathrop—the group of artists now known as the New Hope School of Landscape Painting, or the New Hope Impressionists.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, American impressionism was in full swing and highly popular. By 1916, Folinsbee’s reputation had grown, extending beyond the National Academy of Design in New York to Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and Houston, where his works were regularly included in annual exhibitions of contemporary American art. Folinsbee’s increasing stature in American art was recognized by the National Academy in 1919, when he was elected an associate member at the age of twenty-seven (he became a full academician in 1928).

If Folinsbee is normally associated with the New Hope School and its impressionist style, the expressive work of his middle and later years, though based on principles learned early on, are highly individualistic and subscribe to no style but Folinsbee’s own. After a trip to England and France in 1926, during which the artist visited museums and galleries, painted and sketched, Folinsbee abandoned much of the impressionist approach of the New Hope School.

By the late 1930s, the change in Folinsbee’s style was evident. His brush strokes loosened and lengthened. The shimmering, gem-like colors and bright light that characterized his early work were replaced by dramatic contrasts in light and dark, and with color that was deeper and more intense. Russell Lynes asserted that the artist’s best work was created from this moment on. "After he escaped from the formulas that permeated the Impressionists,” Lynes wrote, Folinsbee’s “brush became more flowing, bolder, surer, and more personal, more concerned with contour and bones than with skin."

Perhaps the artist’s contact with Maine had something to do with this transformation. Beginning in the mid-1930s, Folinsbee and his family spent their summers in Maine, and in 1949 they bought an old farmhouse, Murphy’s Corner, on Montsweag Bay near Wiscasset. As his son-in-law Peter G. Cook observed, after the dramatic contrasts in weather, light, and landscape of Maine, the Pennsylvania countryside seemed a bit tame. It was Maine that captured the imagination of his later years, and works like Burnt Coat Harbor, Maine Moonlight, and Off Seguin (Ellingwood Rock), for which he received the Palmer Marine Prize at the National Academy in 1952, are evocative of weathered towns and harsh summer storms along the Maine coast. These works reflected Folinsbee's maturation into a painter who captured the mood of his surroundings in his own distinctive way.

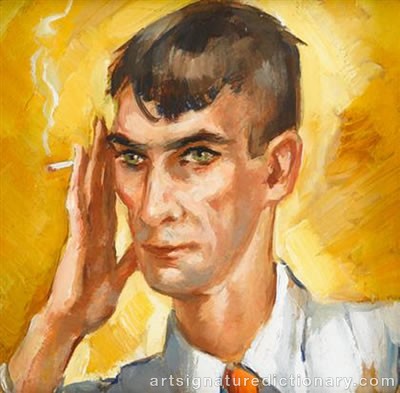

Folinsbee was also an accomplished painter of the figure, primarily portraits, both commissioned as well as those of anyone nearby who might willingly agree to be his model for an hour or two. Over his long career, he painted bankers, educators, doctors, colleagues, students, and fellow Centurions. (His antic depictions of the activities at the Century Association in New York, painted upon the urging of his wife Ruth who was eager to know what went on there, illustrate Folinsbee's sense of humor, charisma, and friendships with other artists; they also provide a behind-the-scenes peek at the Century decades before women were admitted as members.) Similar caricatures of family life and social activities were caught on paper or canvas by Folinsbee—an artist who never seems to have been at a loss for a way to capture the world around him. This aspect of his work is far from inconsequential, for it demonstrates the meeting of discerning eye and generosity of spirit that gave such a unique character to John Folinsbee’s life and art.

Folinsbee was represented by Ferargil Gallery in New York for nearly forty years years (1917-1953), but he disliked the commercial aspects of the art world. When Ferargil Gallery closed, Folinsbee chose not to become affiliated with another gallery, a choice that, while commendable for its independence, limited public exposure to his work. Although he continued to exhibit widely, critical notice of his work was minimal during the final three decades of his life. Even so, Folinsbee’s achievements as an artist were recognized repeatedly in the form of national prizes and awards from institutions such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Rhode Island School of Design, and the Carnegie Museum of Art; in 1953 he was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters. His work is represented in numerous private and public collections, including The Corcoran Gallery of Art and The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.; The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; The New Jersey State Museum; and the Farnsworth Museum of Art in Rockland, ME.

Source: http://www.folinsbee.org/about

Explore other artists

Discover other notable artists who were contemporaries of John Fulton FOLINSBEE. These artists worked during the same period, offering valuable insights into artistic movements, signature styles, and authentication practices. Exploring related artists makes it easier to recognize common characteristics and artistic conventions of their era.